Could COVID have provided the boost needed to push humanitarian assistance back to the local level?

For years the term localization has bounced around in development discussions with little real-world implementation. Yet, COVID restrictions coupled with renewed global awareness might be changing the playing field, creating new incentives for local and regional development initiatives.

What’s at Issue

Localization in the context of development addresses the sources of power, and the centers of decision making. In the past, these decisions have generally been centralized in the western/northern hemisphere where donors and humanitarian workers discuss the process of development for low- and middle-income countries with only limited input from those affected.

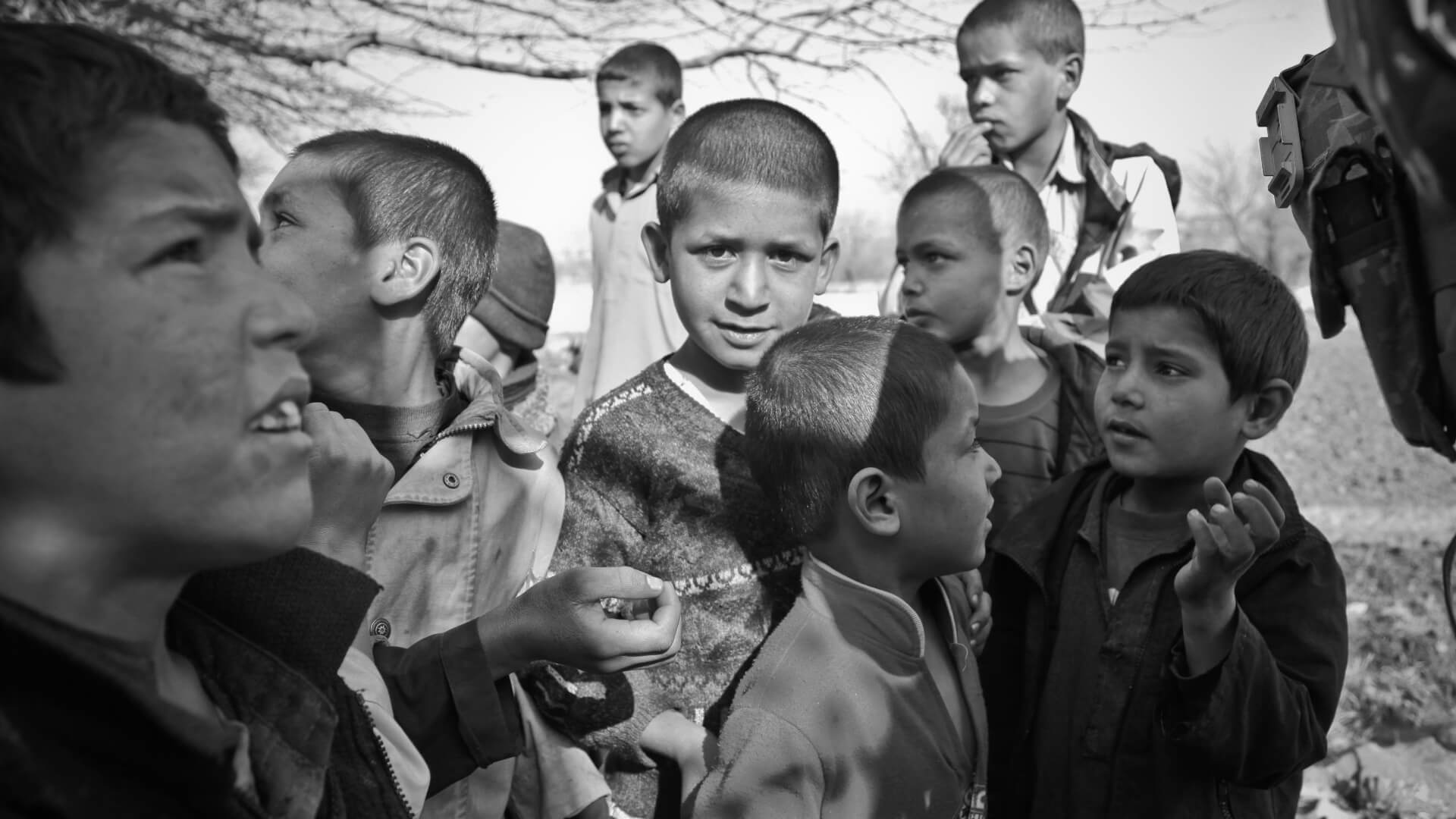

At its root, the question of localization is a question of power dynamics. As the Red Cross puts it, “Often when people hear the word ‘humanitarian’ they imagine a globe-trotting foreigner swooping into a country affected by a crisis and saving the day.” Yet this image is far from the actual realities of humanitarian and developmental work where dedicated local actors bear the burden of program implementation on the ground.

The Macro View

In 2016, a group of the largest humanitarian donors and development organizations signed the Grand Bargain, an agreement by all signatories to allocate at least 25 percent of all humanitarian and development resources to local and national actors. The agreement represented a recognition by actors in the development sphere that revolving-door cultures based in Washington D.C., New York, Paris, London, and other Western Capitals were not efficiently serving the goals of development. Nor was it authentically respecting the rights of Low- and Middle-Income Countries where development initiatives focused. As of April 2021, 25 percent of this goal had yet to be realized.

As a term, localization contains more than just micro level development from local and national actors. It also hits on a salient new discussion of decolonization and equality. It opens discussions about the historic Western-centric vision of most development organizations and the lack of input for those who have been the focus of development projects. In the academic sphere, debate oscillates between the position that localization should transition from an industry dominated by Western perspectives and actors to the position that the field needs a complete makeover as a part of the decolonization approach.

The Stakes

Getting development right (or getting it wrong) has sweeping implications for the international community and especially for the states most in need of financial and infrastructural aid. The past decade has seen the consequences of wealthy nations vying for influence in less developed countries while the “beneficiaries” of aid play out their limited hand in an effort to maintain limited sovereignty.

The current geopolitical east-west division with small, middle-, and low-income states positioned to choose sides has obvious relation to questions of sovereignty and the ability to maintain local and national decision making power. But devolving power to local and national actors will mean the cession of power from the northern hemisphere to the southern, something organizations have been reluctant to do in the past.

State of Play

The COVID-19 pandemic and its accompanying limitations on mobility forced many humanitarian organizations to practice exactly what the logics of localization demand. In absence of international mobility, local actors were required to pick up roles that had been occupied by outside actors. Only time will tell if this trend remains as the physical restraint imposed by the pandemic dissolves. In real terms, localization will leave “winners” and “losers” through the redistribution of activities.

The Look Ahead

The forces that drive localization have human rights and (especially the right to self-determination) on their side. On the other hand, many vested interests incentivize the maintenance of the status quo in the development and humanitarian sphere. As far as decolonization and power shift, the cat’s out of the bag for the western dominated space, the smoothness of the transition will depend on organizations ability to let go and to adapt.

In Canada, for example, localization and the decolonization of development assistance is now becoming a common point of discussion among practitioners, and with government agencies with a view towards co-developing inclusive roadmaps to realize a collective vision of social justice as a driver of effective development.

The task is daunting though by no means, insurmountable. Through COVID, the development community, inclusive of practitioners and government agencies worked to implement a range of solutions and workarounds to ensure that development and humanitarian assistance could continue and that communities and partners the world over remained at the top of our development agenda.

Organizations like the Canadian Association of International Development Professionals (CAIDP-RPCDI), Cooperation Canada amongst a growing number of influencers are working with Global Affairs Canada and other government agencies on Canada’s path forward.

Time will tell if conversation translates into action, and ultimately impact but what is certain is the commitment to change.